The No-Plan Vacation: 4 Days. In Tokyo. No Itinerary. Just Letting Go.

Catherine Price took off for Tokyo with no guidebook and a wacky idea: Let strangers decide every detail of her trip. Four days, 29 brief encounters, one collapsible bicycle, eight octopus balls, 600 flesh-eating fish, one goma fire ceremony, and too much fried food later, she'd discovered the joy in letting go.

It was Friday night in Shinjuku, a Tokyo neighborhood famous for neon signs, subterranean shopping malls, and rent-by-the-hour lodgings known as love hotels. In crowded bars, people tipped back beers and sang karaoke. Young men with black jackets and gelled hair stood on street corners, offering menus of available escorts to passersby. In the midst of the action was a store window, covered except for a narrow strip of glass. If you were to have stopped and looked through it, you would have seen something strange: my legs, submerged to the ankles, with 600 flesh-eating fish feasting on my feet. This is the story of how I got there.

Like many people, I approach vacations with a level of preparation appropriate for a medical licensing exam—poring over Internet reviews, reading guidebooks cover to cover, and studying maps so I'm oriented from the moment my plane touches down. I research, I plan, I strategize, transforming my trips into long to-do lists I must conquer in order for them to be judged a success.

This tendency was in full effect during a recent week my husband and I spent on Kauai, when I broke the island into quadrants and made long lists of every activity we should do while "relaxing" in paradise. It was exhausting, and somewhere in the process, I started to ask myself why I was doing this. What was I trying to accomplish? What if, instead of meticulously planning, I were to just show up in a new place and let the experience unfold? By stage-managing every detail, I realized, I was ruining one of the best parts of travel: the adventure.

So I decided to take a different approach. I would go on a trip in which I relinquished control. No guidebook, no Internet research, no list of things to see or do. Instead, I would base all my activities, from where I stayed to what I ate or saw, on the recommendations of strangers. Even the destination would be chosen by someone else.

I started by approaching a woman in the fiction section of a San Francisco bookstore and asking her to tell me the most interesting place she'd ever been. She responded, "I love Tokyo," and two weeks later, I boarded a flight. I had a map. That was it.

The ambition of this project didn't fully sink in until the plane took off and I realized I was going to have to ask a stranger where to bunk. At first that made me nervous—aren't strangers the same people who steal wallets and kidnap children? But then I looked at the passengers around me. A woman in the next row wore a bumblebee neck pillow. The girl next to me had adorned each long, fake fingernail with a plastic Hello Kitty charm, as if worried a customs agent might demand a finger puppet show. These, I realized, were not the strangers my mother had warned me about.

The problem with guidebooks

I decided to cast my net wide, and asked a flight attendant to make an announcement to the entire cabin, requesting that people ring their call bells if they could recommend a hotel for the night. I imagined the plane lighting up like a Christmas tree as, one by one, my fellow travelers suggested their favorite Tokyo lodgings or offered keys to their unused pieds-á-terre.

The flight attendant politely informed me that the other passengers had not signed up to be my personal travel agents. But he offered to make up for it by consulting with the rest of the Tokyo-based crew. Several minutes later, he found me in the darkened cabin and handed me a piece of paper with suggestions, including "Asakusa."

"This is my neighborhood," he said, introducing himself as Yori. "And this," he pointed at a different word, "is a hostel popular with backpackers." I hadn't even arrived in Tokyo and I had already learned two important lessons. First, it's not that scary to ask people for help. Second, I should dress better.

When I asked Barry Glassner, PhD, sociologist and author of The Culture of Fear, why we love guidebooks so much, he hypothesized that it's because relying on experts alleviates our fear of the unknown and makes us feel more in control. It's an approach that makes total sense, except for one thing: It's an ineffective way to plan a fun trip.

The problem with guidebooks has to do with what psychologists call affective forecasting—our ability to predict our emotional (that is, "affective") reaction to a future event. It's a skill at which we're not particularly good. We overestimate how much a positive event will improve our lives; we underestimate our ability to bounce back from hardship. And when it comes to travel, we're likely to be remarkably bad at predicting how much we'll enjoy the very experiences we've so carefully researched. "People have the notion that if they just gather the right information themselves, they'll make a better prediction of their reaction than they would if they tried to replicate the good experiences of others," says Matt Killingsworth, who runs a project out of Harvard called TrackYourHappiness.org. "But we've found the opposite to be true."

The key, Killingsworth insists, is that bit about "replicating the good experiences of others"—instead of basing our decisions on our own research and analysis, we should just ask other people whether they had a good time. He's got ample research to back this up, but I still fall into the large camp of people who find it hard to believe that strangers could be better than a guidebook at predicting what I'll like.

So I was surprised when I emerged from the train station at Asakusa to find that in this case, Killingsworth—or at least the flight attendant—might have been right: The neighborhood was in northeast Tokyo, a subway ride from downtown, and would never have jumped out at me on a map. But it was perfect. Instead of the high-rises and endless brand-name stores that characterize downtown, Asakusa was filled with charismatic pedestrian streets lined with small shops and restaurants, and was home to the Sensoji temple, the oldest in Tokyo. After dropping my bags at the hostel—which was clean, if basic—I asked for a restaurant recommendation in English from a young mother on the street and ended up in a small restaurant that specialized in tempura. Soon I was digging into the waitress's favorite dish: a bowl of fried shrimp on top of rice. It wasn't the best tempura I'd ever had, but I didn't care. Alone in a strange city on my first night in town, I felt inspired by my experiences thus far—and excited about what might happen next.

"Getting up before dawn to watch a tuna auction is not something I normally do"

The flight attendant politely informed me that the other passengers had not signed up to be my personal travel agents. But he offered to make up for it by consulting with the rest of the Tokyo-based crew. Several minutes later, he found me in the darkened cabin and handed me a piece of paper with suggestions, including "Asakusa."

"This is my neighborhood," he said, introducing himself as Yori. "And this," he pointed at a different word, "is a hostel popular with backpackers." I hadn't even arrived in Tokyo and I had already learned two important lessons. First, it's not that scary to ask people for help. Second, I should dress better.

When I asked Barry Glassner, PhD, sociologist and author of The Culture of Fear, why we love guidebooks so much, he hypothesized that it's because relying on experts alleviates our fear of the unknown and makes us feel more in control. It's an approach that makes total sense, except for one thing: It's an ineffective way to plan a fun trip.

The problem with guidebooks has to do with what psychologists call affective forecasting—our ability to predict our emotional (that is, "affective") reaction to a future event. It's a skill at which we're not particularly good. We overestimate how much a positive event will improve our lives; we underestimate our ability to bounce back from hardship. And when it comes to travel, we're likely to be remarkably bad at predicting how much we'll enjoy the very experiences we've so carefully researched. "People have the notion that if they just gather the right information themselves, they'll make a better prediction of their reaction than they would if they tried to replicate the good experiences of others," says Matt Killingsworth, who runs a project out of Harvard called TrackYourHappiness.org. "But we've found the opposite to be true."

The key, Killingsworth insists, is that bit about "replicating the good experiences of others"—instead of basing our decisions on our own research and analysis, we should just ask other people whether they had a good time. He's got ample research to back this up, but I still fall into the large camp of people who find it hard to believe that strangers could be better than a guidebook at predicting what I'll like.

So I was surprised when I emerged from the train station at Asakusa to find that in this case, Killingsworth—or at least the flight attendant—might have been right: The neighborhood was in northeast Tokyo, a subway ride from downtown, and would never have jumped out at me on a map. But it was perfect. Instead of the high-rises and endless brand-name stores that characterize downtown, Asakusa was filled with charismatic pedestrian streets lined with small shops and restaurants, and was home to the Sensoji temple, the oldest in Tokyo. After dropping my bags at the hostel—which was clean, if basic—I asked for a restaurant recommendation in English from a young mother on the street and ended up in a small restaurant that specialized in tempura. Soon I was digging into the waitress's favorite dish: a bowl of fried shrimp on top of rice. It wasn't the best tempura I'd ever had, but I didn't care. Alone in a strange city on my first night in town, I felt inspired by my experiences thus far—and excited about what might happen next.

"Getting up before dawn to watch a tuna auction is not something I normally do"

Before collapsing in the hostel, I asked a woman who had helped me find a towel what I should do if I woke up early, a likely scenario, since 2 A.M. in Tokyo was 9 A.M. the day before on America's West Coast. She suggested the Tsukiji Market. This wasn't particularly creative—Tsukiji is one of the biggest tourist attractions in the city, as well known as the Empire State Building or Times Square. But at 4 in the morning, what else was I going to do?

When I awoke at 3:30, sans alarm clock, I was tempted to stay in bed on principle—but I fought the urge and headed into the dark. The streets were deserted, the subway uncharacteristically empty, and I was surprised when I walked out of the station into a stream of people sweeping me toward the cavernous market.

Unfortunately for my jet lag, Tsukiji operated at the speed of a stock exchange. Motorized carts barreled down its wet streets in unpredictable directions, forklifts hoisted pallets of sea creatures onto trucks, and no matter where I stood, I was in someone's way. Worried about meeting my doom under a box of soft-shelled crabs, I stuck close to a row of parked trucks and soon entered the main area of the market. Rows of stalls displayed Styrofoam containers of fresh seafood—eels, mackerel, tightly coiled tentacles of octopus—each booth presided over by vendors wearing overcoats to keep out the cold.

The sun had barely begun to rise, but at the back of the market, the daily fish auction was already under way. Dozens of enormous frozen tuna lay on the ground in a large warehouse, each with a round steak cut from its tail and attached to its body by a piece of colored plastic rope. Buyers in black galoshes moved methodically from tuna to tuna, jabbing the exposed flesh of the tail with hook-tipped wooden sticks to determine the fattiness of the meat. As I watched, a man climbed atop a small box and began frantically ringing a small bell. Then, in a torrent of Japanese and hand signals, he auctioned off the fish.

Despite the other tourists packed around me, I felt exhilarated, as if I'd stumbled onto something secret. The most likely reason for this sense of achievement—an emotion I felt repeatedly over the course of the trip—was that getting up before dawn to watch a tuna auction is not something I normally do. "At first glance, challenge and novelty may seem like things to avoid," explains Gregory Berns, MD, PhD, a neuroeconomist at Emory University, in his book Satisfaction: The Science of Finding True Fulfillment. "But they are the exact ingredients that make for a satisfying experience." This rang true. The downside of traveling with no plans was that everything took effort. But the upside was that each time I managed to, say, feed myself, I felt I'd accomplished something big.

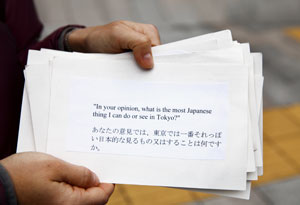

I should pause here to explain my method. Figuring that most people's English would be as nonexistent as my Japanese, I'd had a fluent friend translate an introduction and several key questions, which I printed out on oversize cards and carried in my bag. If I wanted to ask people their favorite dish or sight to see, I would show them the card, have them write down the answer, and have someone else tell me what it said. (It was an excellent system overall, but beware Google Translate. Based on its software, my introductory card said: "Put fear! My name is Kasharin Price.... We are forced to travel to ask your opinion of the residents there, since the threshold and what to look funny or what should I do.")

"I am American, and I want to eat breakfast!"

When I awoke at 3:30, sans alarm clock, I was tempted to stay in bed on principle—but I fought the urge and headed into the dark. The streets were deserted, the subway uncharacteristically empty, and I was surprised when I walked out of the station into a stream of people sweeping me toward the cavernous market.

Unfortunately for my jet lag, Tsukiji operated at the speed of a stock exchange. Motorized carts barreled down its wet streets in unpredictable directions, forklifts hoisted pallets of sea creatures onto trucks, and no matter where I stood, I was in someone's way. Worried about meeting my doom under a box of soft-shelled crabs, I stuck close to a row of parked trucks and soon entered the main area of the market. Rows of stalls displayed Styrofoam containers of fresh seafood—eels, mackerel, tightly coiled tentacles of octopus—each booth presided over by vendors wearing overcoats to keep out the cold.

The sun had barely begun to rise, but at the back of the market, the daily fish auction was already under way. Dozens of enormous frozen tuna lay on the ground in a large warehouse, each with a round steak cut from its tail and attached to its body by a piece of colored plastic rope. Buyers in black galoshes moved methodically from tuna to tuna, jabbing the exposed flesh of the tail with hook-tipped wooden sticks to determine the fattiness of the meat. As I watched, a man climbed atop a small box and began frantically ringing a small bell. Then, in a torrent of Japanese and hand signals, he auctioned off the fish.

Despite the other tourists packed around me, I felt exhilarated, as if I'd stumbled onto something secret. The most likely reason for this sense of achievement—an emotion I felt repeatedly over the course of the trip—was that getting up before dawn to watch a tuna auction is not something I normally do. "At first glance, challenge and novelty may seem like things to avoid," explains Gregory Berns, MD, PhD, a neuroeconomist at Emory University, in his book Satisfaction: The Science of Finding True Fulfillment. "But they are the exact ingredients that make for a satisfying experience." This rang true. The downside of traveling with no plans was that everything took effort. But the upside was that each time I managed to, say, feed myself, I felt I'd accomplished something big.

I should pause here to explain my method. Figuring that most people's English would be as nonexistent as my Japanese, I'd had a fluent friend translate an introduction and several key questions, which I printed out on oversize cards and carried in my bag. If I wanted to ask people their favorite dish or sight to see, I would show them the card, have them write down the answer, and have someone else tell me what it said. (It was an excellent system overall, but beware Google Translate. Based on its software, my introductory card said: "Put fear! My name is Kasharin Price.... We are forced to travel to ask your opinion of the residents there, since the threshold and what to look funny or what should I do.")

"I am American, and I want to eat breakfast!"

Other than seeking variety, I had no criteria for the people I approached—the first person who made eye contact with me usually got a card. Such was the case with a woman selling greens in a produce market next to Tsukiji. One smile tossed my way, and I thrust a question into her hands. It said, "What is your favorite restaurant?" so I tried to explain, via hand gestures, that what I actually meant was "I am hungry for breakfast but already had a large bowl of shrimp tempura for dinner, so could you recommend something a little lighter?" She shook her head shyly and handed it back.

Meanwhile, a man had walked over and was inspecting herbs. In his early 40s, with close-cropped hair and wire-rimmed glasses, he glanced up from his parsley to find me staring at him, and responded with a word I'd never expected to hear from a Japanese herb buyer in the Tokyo fish market: "Bonjour."

He took my card when I offered it and tried to respond in English but kept lapsing into French, a language I hadn't attempted to speak since high school. Figuring Tsukiji was a safe place to practice my accent, I jumped in, and soon the man and I were communicating in a pidgin of languages and hand signals. "Je suis Americaine, et je veux manger le petit déjeuner," I told him. I am American, and I want to eat breakfast!

The man, whose name was Yoshi, paid for his herbs and then, like many other people I met that week, stopped what he was doing and gestured for me to follow him. We darted through the river of whizzing carts, and then he pointed me toward a street of hole-in-the-wall shops with pictures of noodles in their windows. But instead of disappearing back into the crowd, he kept chatting. It turned out that he was the chef at Amor, a French-and-Spanish-inspired restaurant so close to my hostel that I'd passed it that morning—a remarkable coincidence, considering that Tokyo covers more than 800 square miles. I should come for dinner, he said, jotting down my cell phone number so that his wife—whose English he claimed was better than his—could give me a call. Then he slipped back into the market to finish shopping.

Despite our fear of strangers, there are times when we share surprisingly intimate details with people we don't know—like when we exchange life stories with the person sitting next to us on a plane. Sociologists call these interactions fleeting relationships, and, on the surface, they appear to be nothing more than pleasant ways to pass the time. But according to Calvin Morrill, PhD, coeditor of a collection of studies on personal relationships in public spaces called Together Alone, these interactions are more than just enjoyable: They act as the "connective tissue" that helps societies function and makes the public realm a nicer—and potentially safer—place to be. A culture that mistrusts strangers is less likely to encourage such relationships, which, according to Morrill's logic, may have the ironic effect of making that society less safe.

I've always considered such brief encounters one of the best parts of traveling—they give you a personal glimpse into a foreign culture that a guidebook can't provide. So I was excited when I arrived at Amor to see Yoshi—now wearing a black apron and white chef's hat—enthusiastically waving at me through the restaurant's glass door. He explained that he had just been describing our conversation to his wife, Maiko. A petite woman with heavy bangs and a black-and-white-striped turtleneck, she greeted me in English and motioned for me to have a seat.

I sat at the bar, which was decorated with a model train set left over from the previous owner. With one station in Asakusa and the other in a German Alpine village, the train was an odd addition to a French-Spanish restaurant in Tokyo; if I'd been in a more poetic mood, I might have contemplated the symbolic connection between my interactions with Yoshi and the international train travel taking place on the counter. But instead I was concerned with the menu. That morning I'd somehow missed the noodles and ended up with two more enormous fried shrimp. In the afternoon I had asked a teller at a Citibank if she could recommend a place for lunch and found myself in a sixth-floor kushikatsu restaurant, a Japanese specialty that roughly translates as "deep-fried skewer." It involves taking otherwise healthy ingredients—mushrooms, tofu, asparagus spears—and turning them into the Japanese equivalent of a corn dog.

Luckily, Maiko and Yoshi refrained from making me anything deep-fried. Instead, Yoshi emerged from the kitchen with a multicourse meal that included everything from smoked salmon crepes to sea urchin consommé. He and Maiko hung out behind the bar as I ate, telling me about their years in France, where Yoshi worked as a chef and Maiko as a journalist. They had never wanted to fall into traditional jobs and thought that traveling had opened them up to pursuing less conventional professions. We traded e-mail addresses, and I encouraged them to contact me if they ever came to America. "Je suis très content—I am very happy," Yoshi said at the end of the evening as we said goodbye. I agreed.

"Sometimes we should just let our hair down and experience life"

Meanwhile, a man had walked over and was inspecting herbs. In his early 40s, with close-cropped hair and wire-rimmed glasses, he glanced up from his parsley to find me staring at him, and responded with a word I'd never expected to hear from a Japanese herb buyer in the Tokyo fish market: "Bonjour."

He took my card when I offered it and tried to respond in English but kept lapsing into French, a language I hadn't attempted to speak since high school. Figuring Tsukiji was a safe place to practice my accent, I jumped in, and soon the man and I were communicating in a pidgin of languages and hand signals. "Je suis Americaine, et je veux manger le petit déjeuner," I told him. I am American, and I want to eat breakfast!

The man, whose name was Yoshi, paid for his herbs and then, like many other people I met that week, stopped what he was doing and gestured for me to follow him. We darted through the river of whizzing carts, and then he pointed me toward a street of hole-in-the-wall shops with pictures of noodles in their windows. But instead of disappearing back into the crowd, he kept chatting. It turned out that he was the chef at Amor, a French-and-Spanish-inspired restaurant so close to my hostel that I'd passed it that morning—a remarkable coincidence, considering that Tokyo covers more than 800 square miles. I should come for dinner, he said, jotting down my cell phone number so that his wife—whose English he claimed was better than his—could give me a call. Then he slipped back into the market to finish shopping.

Despite our fear of strangers, there are times when we share surprisingly intimate details with people we don't know—like when we exchange life stories with the person sitting next to us on a plane. Sociologists call these interactions fleeting relationships, and, on the surface, they appear to be nothing more than pleasant ways to pass the time. But according to Calvin Morrill, PhD, coeditor of a collection of studies on personal relationships in public spaces called Together Alone, these interactions are more than just enjoyable: They act as the "connective tissue" that helps societies function and makes the public realm a nicer—and potentially safer—place to be. A culture that mistrusts strangers is less likely to encourage such relationships, which, according to Morrill's logic, may have the ironic effect of making that society less safe.

I've always considered such brief encounters one of the best parts of traveling—they give you a personal glimpse into a foreign culture that a guidebook can't provide. So I was excited when I arrived at Amor to see Yoshi—now wearing a black apron and white chef's hat—enthusiastically waving at me through the restaurant's glass door. He explained that he had just been describing our conversation to his wife, Maiko. A petite woman with heavy bangs and a black-and-white-striped turtleneck, she greeted me in English and motioned for me to have a seat.

I sat at the bar, which was decorated with a model train set left over from the previous owner. With one station in Asakusa and the other in a German Alpine village, the train was an odd addition to a French-Spanish restaurant in Tokyo; if I'd been in a more poetic mood, I might have contemplated the symbolic connection between my interactions with Yoshi and the international train travel taking place on the counter. But instead I was concerned with the menu. That morning I'd somehow missed the noodles and ended up with two more enormous fried shrimp. In the afternoon I had asked a teller at a Citibank if she could recommend a place for lunch and found myself in a sixth-floor kushikatsu restaurant, a Japanese specialty that roughly translates as "deep-fried skewer." It involves taking otherwise healthy ingredients—mushrooms, tofu, asparagus spears—and turning them into the Japanese equivalent of a corn dog.

Luckily, Maiko and Yoshi refrained from making me anything deep-fried. Instead, Yoshi emerged from the kitchen with a multicourse meal that included everything from smoked salmon crepes to sea urchin consommé. He and Maiko hung out behind the bar as I ate, telling me about their years in France, where Yoshi worked as a chef and Maiko as a journalist. They had never wanted to fall into traditional jobs and thought that traveling had opened them up to pursuing less conventional professions. We traded e-mail addresses, and I encouraged them to contact me if they ever came to America. "Je suis très content—I am very happy," Yoshi said at the end of the evening as we said goodbye. I agreed.

"Sometimes we should just let our hair down and experience life"

In their widely acclaimed 2009 book Connected: The Surprising Power of Our Social Networks and How They Shape Our Lives, James Fowler, PhD, and Nicholas Christakis, MD, PhD, investigate how our friends' and acquaintances' behavior affects our own. According to their research, for example, if a friend's friend's friend gains weight, you're more likely to as well. Thankfully, total strangers don't usually wield much influence over our pants size. But they are useful for something else: gathering information. "Close friends tend to have exactly the same information you do," Fowler explains. "By making contacts with strangers, you increase the likelihood you'll get information you never had before."

By approaching only strangers, I was definitely getting new information. So the question came down to what type of stranger would be the most useful. Was it someone with expertise, like a 75-year-old Tokyo native? Or would it be better to speak to a tourist closer to my age, whose tastes were likely more similar to my own?

I came up with a simple solution: Try both. First, I sought the familiar. Two young Americans at the tuna auction had told me their favorite activity had been riding bicycles around Tokyo. So the next morning, I set off for CoolBike, a rental place nearby.

Unlike the strong-thighed, greasy-fingernailed mechanics who populate American bike shops, CoolBike's staff—or at least the three people who ran into the street when I rang their buzzer—looked like they'd come from a conference call. The woman wore a wool skirt and blouse. One man sported stylish glasses and a well-tailored suit, and the second man, also dressed for the office, had rushed out of the building so fast that he was still wearing plastic slippers. They seemed both thrilled to have a customer and confused about what was supposed to happen next.

"Do you have a bike map?" I asked. The woman glanced at her coworkers, then looked at me quizzically. "You know, a route?" I said. I pulled a map out of my bag and pointed at it with a questioning expression. "Ah," she said. "Where do you want to go?"

I handed her my introductory card ("Put fear! My name is Kasharin!") and asked where she thought I should go.

The woman and her colleagues began debating routes. Should they recommend the Imperial Palace? Or the Tokyo Dome, a puffy-topped sports stadium next to an amusement park? Eventually they settled on a circular path that hit both and sent me on my way with an even stranger imperative: Find an octopus in a bowl.

I had no idea where—or, more important, why—I was to find a domesticated octopus. But I had a more immediate problem: how to navigate the streets of Tokyo on a collapsible bike. I tried staying to the right, American-style, then switched to the left to match Japanese traffic. Neither worked. Pedestrians gave me nasty looks, and I nearly sideswiped an elderly woman when she paused to open an umbrella.

The area around the Imperial Palace was quieter, and I tooled around until I came upon an older Japanese couple sitting on camp stools outside a palace gate, drawing in sketchbooks. They seemed the perfect candidates for the second stage of my experiment—getting advice from older Tokyo natives—so I pulled up and gave them one of my favorite cards: "What is the most Japanese thing I can do or see in Tokyo?"

The husband grabbed my pen, wrote something on the back of the card, confirmed it with his wife, and then launched into a fast-paced monologue, chuckling, gesticulating, and pausing for laughs.

The man's suggestion turned out to be rakugo, a form of Japanese comedy. His performance in the park made me think it must be similar to American stand-up—a boozy bar, a boisterous crowd—but when I arrived at his favorite venue later that night, it was a clean theater brightly lit with paper lanterns. A series of men in kimonos knelt on a purple pillow onstage and told long, humorous stories with no props other than a small cloth and a folded paper fan. These monologues were broken up by acts bordering on vaudeville. My favorite performer was a guy who did imitations of bullet trains on a violin, then put on tap shoes and danced to "Take Me Out to the Ball Game."

So which was better, the suggestion from the Americans or from the Japanese natives? Neither would likely have made it onto a top ten tourist list. But for my purposes, that didn't matter. "It's okay if you don't always end up at the 'best' movie or the 'best' restaurant," said Sheena Iyengar, PhD, author of The Art of Choosing. "Sometimes we should just let our hair down and experience life."

"It felt as if I were in a real-life Choose Your Own Adventure"

By approaching only strangers, I was definitely getting new information. So the question came down to what type of stranger would be the most useful. Was it someone with expertise, like a 75-year-old Tokyo native? Or would it be better to speak to a tourist closer to my age, whose tastes were likely more similar to my own?

I came up with a simple solution: Try both. First, I sought the familiar. Two young Americans at the tuna auction had told me their favorite activity had been riding bicycles around Tokyo. So the next morning, I set off for CoolBike, a rental place nearby.

Unlike the strong-thighed, greasy-fingernailed mechanics who populate American bike shops, CoolBike's staff—or at least the three people who ran into the street when I rang their buzzer—looked like they'd come from a conference call. The woman wore a wool skirt and blouse. One man sported stylish glasses and a well-tailored suit, and the second man, also dressed for the office, had rushed out of the building so fast that he was still wearing plastic slippers. They seemed both thrilled to have a customer and confused about what was supposed to happen next.

"Do you have a bike map?" I asked. The woman glanced at her coworkers, then looked at me quizzically. "You know, a route?" I said. I pulled a map out of my bag and pointed at it with a questioning expression. "Ah," she said. "Where do you want to go?"

I handed her my introductory card ("Put fear! My name is Kasharin!") and asked where she thought I should go.

The woman and her colleagues began debating routes. Should they recommend the Imperial Palace? Or the Tokyo Dome, a puffy-topped sports stadium next to an amusement park? Eventually they settled on a circular path that hit both and sent me on my way with an even stranger imperative: Find an octopus in a bowl.

I had no idea where—or, more important, why—I was to find a domesticated octopus. But I had a more immediate problem: how to navigate the streets of Tokyo on a collapsible bike. I tried staying to the right, American-style, then switched to the left to match Japanese traffic. Neither worked. Pedestrians gave me nasty looks, and I nearly sideswiped an elderly woman when she paused to open an umbrella.

The area around the Imperial Palace was quieter, and I tooled around until I came upon an older Japanese couple sitting on camp stools outside a palace gate, drawing in sketchbooks. They seemed the perfect candidates for the second stage of my experiment—getting advice from older Tokyo natives—so I pulled up and gave them one of my favorite cards: "What is the most Japanese thing I can do or see in Tokyo?"

The husband grabbed my pen, wrote something on the back of the card, confirmed it with his wife, and then launched into a fast-paced monologue, chuckling, gesticulating, and pausing for laughs.

The man's suggestion turned out to be rakugo, a form of Japanese comedy. His performance in the park made me think it must be similar to American stand-up—a boozy bar, a boisterous crowd—but when I arrived at his favorite venue later that night, it was a clean theater brightly lit with paper lanterns. A series of men in kimonos knelt on a purple pillow onstage and told long, humorous stories with no props other than a small cloth and a folded paper fan. These monologues were broken up by acts bordering on vaudeville. My favorite performer was a guy who did imitations of bullet trains on a violin, then put on tap shoes and danced to "Take Me Out to the Ball Game."

So which was better, the suggestion from the Americans or from the Japanese natives? Neither would likely have made it onto a top ten tourist list. But for my purposes, that didn't matter. "It's okay if you don't always end up at the 'best' movie or the 'best' restaurant," said Sheena Iyengar, PhD, author of The Art of Choosing. "Sometimes we should just let our hair down and experience life."

"It felt as if I were in a real-life Choose Your Own Adventure"

Over the course of the next few days, I continued to drift into experiences that I never would have had without strangers' help. After the rakugo show, I met a former Seiko board member who was celebrating his 76th birthday with his wife at a sushi restaurant called Tuna People. The man, who spoke perfect English, gave me careful directions to a temple in his neighborhood north of Tokyo where monks put on a theatrical fire ritual called a goma ceremony several times a day. That night I asked the head sushi chef for his favorite dish, and after giving me both an unsolicited recommendation for an art museum and a plate of julienned raw squid, he presented me with a row of nigiri topped with uncooked mollusks. Following the suggestion of a young television host I met on the street, I sought out a public bath, and spent a morning soaking in a pool of steaming hot water backed by a mosaic of a blonde mermaid. I asked an artsy-looking woman with highlighted hair and a fake leopard collar for her favorite lunch place and ended up in a Hawaiian-themed burger restaurant where the staff greeted me with "Aloha."

It felt as if I were in a real-life Choose Your Own Adventure. I never knew what might happen next. I went to the Electric Power Historical Museum, experimented with something called an aroma computer, visited a climbing gym, tried on a trendy wig, took photos of myself in a subterranean photo-booth arcade, and rode a subway train at rush hour (yes, that was actually a suggestion). I approached men, women, old people, young people, visitors from Taiwan and Australia, toy store employees, Starbucks baristas, art students, bank tellers, and a young woman dressed as a bunny rabbit. I even figured out the mystery of the octopus in a bowl: The term was actually octopus ball, and referred to takoyaki, round, delicious dumplings with a chunk of octopus in the center. I tried, in short, to do everything people told me to do.

If you'd talked to me before the trip, I'd have predicted that my experiment would be stressful. And indeed, if it had lasted longer, my excitement might well have turned to anxiety and annoyance. But instead, forbidding myself to plan for the future allowed me to be more grounded in the present; I felt a level of calmness I rarely do in my normal life, where I'm supported not by strangers but by a loving network of family and friends. Why was this—and how could I bring the feeling home?

Part of the answer lies, I suspect, in a parable James Baraz wrote about in Awakening Joy: 10 Steps That Will Put You on the Road to Real Happiness. He talks about a trap used to catch monkeys in Asia in which a coconut with a hole drilled at one end is filled with candy and tied to a stake. A monkey, smelling the treats, reaches inside and grabs a fistful. Excited, it tries to run off—and then encounters the genius of the trap: The hole is big enough for an empty hand but not one that's full. It doesn't matter whether the hand in question is holding sweets—to escape the trap, you just need to let go. Unfortunately, says Baraz, it's a rare monkey that figures that out.

I am not usually that monkey. But something about my week in Tokyo gave me a glimpse of how freeing it could be to let go of my desire for control. I wasn't concerned about logistics or worried about what would happen the next hour or the next day; I simply had faith that things would work out. Ironically, being immersed in a state of insecurity made me feel less scared.

The author's last day in Tokyo

It felt as if I were in a real-life Choose Your Own Adventure. I never knew what might happen next. I went to the Electric Power Historical Museum, experimented with something called an aroma computer, visited a climbing gym, tried on a trendy wig, took photos of myself in a subterranean photo-booth arcade, and rode a subway train at rush hour (yes, that was actually a suggestion). I approached men, women, old people, young people, visitors from Taiwan and Australia, toy store employees, Starbucks baristas, art students, bank tellers, and a young woman dressed as a bunny rabbit. I even figured out the mystery of the octopus in a bowl: The term was actually octopus ball, and referred to takoyaki, round, delicious dumplings with a chunk of octopus in the center. I tried, in short, to do everything people told me to do.

If you'd talked to me before the trip, I'd have predicted that my experiment would be stressful. And indeed, if it had lasted longer, my excitement might well have turned to anxiety and annoyance. But instead, forbidding myself to plan for the future allowed me to be more grounded in the present; I felt a level of calmness I rarely do in my normal life, where I'm supported not by strangers but by a loving network of family and friends. Why was this—and how could I bring the feeling home?

Part of the answer lies, I suspect, in a parable James Baraz wrote about in Awakening Joy: 10 Steps That Will Put You on the Road to Real Happiness. He talks about a trap used to catch monkeys in Asia in which a coconut with a hole drilled at one end is filled with candy and tied to a stake. A monkey, smelling the treats, reaches inside and grabs a fistful. Excited, it tries to run off—and then encounters the genius of the trap: The hole is big enough for an empty hand but not one that's full. It doesn't matter whether the hand in question is holding sweets—to escape the trap, you just need to let go. Unfortunately, says Baraz, it's a rare monkey that figures that out.

I am not usually that monkey. But something about my week in Tokyo gave me a glimpse of how freeing it could be to let go of my desire for control. I wasn't concerned about logistics or worried about what would happen the next hour or the next day; I simply had faith that things would work out. Ironically, being immersed in a state of insecurity made me feel less scared.

The author's last day in Tokyo

My last night in Tokyo fell on a Friday. I spent it in an area called the Golden Gai, a dense grid of alleys lined with tiny drinking holes that had been recommended by the same young man who'd suggested I ride a crowded subway train. The bar I entered had six seats and no standing room, and was presided over by a couple who led double lives as professional voice-over actors for cartoon characters. I chatted with the bartender as her husband sat silently in the corner eating rice crackers.

"What did you do today?" she asked in hesitant English. I'd told her about my project as the bar's other customers—three men in messy business suits—passed around my cards. When I announced that I'd visited a sento—a public bath—she laughed and interrupted me with a flood of Japanese that included two English words: "doctor fish."

It was as if I were listening to AM sports radio—I could tell she was speaking my language but had no idea what she was saying.

"You know," she said, seeing my look of confusion. "Doctor fish." She made a nibbling motion with her fingers to demonstrate. "Eating your feet?"

Eventually, I figured out what she was talking about: a beauty treatment in which you stick your feet into a tank of water and let a special breed of fish nibble off your dead skin. It got its start as a treatment for psoriasis but now, apparently, was attracting a trendier clientele.

This was not what I'd anticipated doing on my last night in Tokyo. Karaoke, maybe. Feet-munching fish, not so much. But what the hell—I'd come this far on other people's suggestions. Why stop now? I had only one question: how to find a school of fish on call at 9 on a Friday night.

But that's the thing—once you realize you can ask people for help, it doesn't take long to find it. The owner gave the name of the spa to one of the businessmen, who made a call and found out the fish were not only on duty until 3 in the morning but were about a block from the bar. Excited, the owner led me around the corner and dropped me off in front of a glass window, through which I could see a tank full of fish nibbling on someone's exposed toes.

I bought my ticket, rinsed my feet in the locker room, and plunked them into the tank. Then began the most ticklish ten minutes of my life as fish swam beneath and between my toes, quivering as they flicked their tiny mouths against my skin.

I doubt many philosophical treatises have been written in the company of doctor fish, but as a Japanese couple joined me in the tank and we giggled at one another (like love, tickling needs no translation), I thought of a second point made by James Baraz that I hoped I could bring home. Learning to trust life, says Baraz, is like learning to swim. First you flail, convinced you're going to drown. Then you notice that if you calm down, it's possible to tread water. Finally, as your movements slow, you realize something much more profound. "When you let go completely and just relax, you find that you are magically held up by the water," Baraz says. "It was ready to support you all the time."

Anatomy of an unplanned adventure: Catherine's Tokyo travels in pictures

"What did you do today?" she asked in hesitant English. I'd told her about my project as the bar's other customers—three men in messy business suits—passed around my cards. When I announced that I'd visited a sento—a public bath—she laughed and interrupted me with a flood of Japanese that included two English words: "doctor fish."

It was as if I were listening to AM sports radio—I could tell she was speaking my language but had no idea what she was saying.

"You know," she said, seeing my look of confusion. "Doctor fish." She made a nibbling motion with her fingers to demonstrate. "Eating your feet?"

Eventually, I figured out what she was talking about: a beauty treatment in which you stick your feet into a tank of water and let a special breed of fish nibble off your dead skin. It got its start as a treatment for psoriasis but now, apparently, was attracting a trendier clientele.

This was not what I'd anticipated doing on my last night in Tokyo. Karaoke, maybe. Feet-munching fish, not so much. But what the hell—I'd come this far on other people's suggestions. Why stop now? I had only one question: how to find a school of fish on call at 9 on a Friday night.

But that's the thing—once you realize you can ask people for help, it doesn't take long to find it. The owner gave the name of the spa to one of the businessmen, who made a call and found out the fish were not only on duty until 3 in the morning but were about a block from the bar. Excited, the owner led me around the corner and dropped me off in front of a glass window, through which I could see a tank full of fish nibbling on someone's exposed toes.

I bought my ticket, rinsed my feet in the locker room, and plunked them into the tank. Then began the most ticklish ten minutes of my life as fish swam beneath and between my toes, quivering as they flicked their tiny mouths against my skin.

I doubt many philosophical treatises have been written in the company of doctor fish, but as a Japanese couple joined me in the tank and we giggled at one another (like love, tickling needs no translation), I thought of a second point made by James Baraz that I hoped I could bring home. Learning to trust life, says Baraz, is like learning to swim. First you flail, convinced you're going to drown. Then you notice that if you calm down, it's possible to tread water. Finally, as your movements slow, you realize something much more profound. "When you let go completely and just relax, you find that you are magically held up by the water," Baraz says. "It was ready to support you all the time."

Anatomy of an unplanned adventure: Catherine's Tokyo travels in pictures

Photo: Jun Takagi