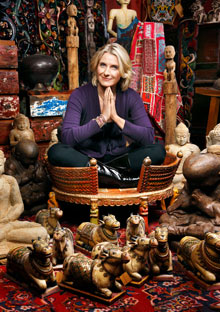

Photo: Ben Baker

As fans of Elizabeth Gilbert's best-selling memoir know, soul-searching across three countries led her to a happy ending with Felipe. Turns out that was just the beginning. Gilbert sat down with Lucy Kaylin to talk about her new book, Committed, and how she made peace with marrying again.

Deploying her crinkly, twinkly smile, Liz Gilbert takes a bite of a red velvet cupcake, then wraps her fingers around a warm cup of tea, as though it's some talismanic thing. She's sitting at the Bridge Café in Frenchtown, New Jersey, the restaurant equivalent of Gilbert herself, with its unpretentious, eager-to-please vibe (tin ceilings, homemade pastries, Jackson Browne on the hi-fi). It's just a few minutes from the old Victorian she shares with her husband of almost three years (known to Gilbert fans as Felipe)—the Brazilian she bedded so transformatively toward the end of Eat, Pray, Love. If that literary juggernaut was a response to Gilbert's brutal divorce, her stirring new book, Committed, is a meditation on marriage: Although she and Felipe never had any intention of formalizing their relationship, Felipe's iffy immigration status—plus a run-in with the Department of Homeland Security—pushed them rather rudely in that direction. Here, Gilbert discusses some of the tasty revelations in Committed—about the trouble with children, the unquantifiable beauty of a man who cooks, and the significance of a certain wine-colored coat.Start reading the interview with Elizabeth Gilbert

Photo: Courtesy of Elizabeth Gilbert

LK: Eat, Pray, Love has sold seven million copies worldwide, and has been translated into 30 languages. Feeling any pressure with this next one?

LG: When somebody has an enormous success in this culture, people start asking two questions, which are "What are you doing now?" and "How are you going to beat that?" And I have to say, I love the assumption that your intention is to beat yourself constantly—that you're in battle against yourself. This sort of cannibalistic self-competition...this is largely why people Britney out.

LK: I'm so glad Britney is finally a verb.

LG: And you can make it a gerund: "I was trying to avoid Britneying out." I think I'm really fortunate that this happened to me when I was in my late 30s, not my early 20s. And it happened on my fourth book, not my first. And it happened after I had already gone through a depression, a divorce, years of therapy, a lot of self-reckoning, a spiritual journey. I was in the lucky situation of knowing who I was. And, more important, who I wasn't.

LK: Meaning what?

LG: Meaning I'm not what's being said about me, either in the highest praise or the highest criticism. I know I'm not a self-indulgent idiot; I also know I'm not the second coming of Deepak Chopra. If I had believed either of those, or both, as some people do when they get famous, that's when the mental illness arrives.

LK: Do you sense with this book that people are expecting Son of Eat, Pray, Love?

LG: People want three things simultaneously from your next endeavor: They love what you did, so they want more of that. But they also want it to be totally different, because you have to show that you're reinventing yourself, à la Madonna. And they want it to be better. The same, different, and better. So, no pressure there. Done and done.

I remember being in English class in college and we were discussing To Kill a Mockingbird. And this pimply-faced 19-year-old boy next to me goes, "Harper Lee—one-hit wonder." [Laughs] And I was like, there's something wrong with that. This isn't a pop song; if you have written the definitive 20th-century tome on racism, compassion, and forgiveness, you can take a pass for the rest of your life, if you want to just garden after that. You know, it's crazy. It's just so nuts.

LK: Before this version of Committed, you had completed a 500-page manuscript that you ultimately trashed. What was wrong with it?

LG: When I went back and looked at the first chapter, I could see so clearly, even sentence by sentence, where it was my authentic, current voice, interspersed with attempts to delight and entertain millions of readers whose names I don't know, by throwing in stuff that I thought they might like. Strained attempts at humor. Strained attempts at goofiness that wasn't really going on during the year I was writing about. It wasn't a goofy year. It was a pretty serious year, you know? It just didn't sound right; it just didn't feel right. So I took some time off, and found that my mind kept going back to the marriage book, just thinking, "I do want to tell this story. I just have to give myself permission to hope that my readers will grow up with me."

LG: When somebody has an enormous success in this culture, people start asking two questions, which are "What are you doing now?" and "How are you going to beat that?" And I have to say, I love the assumption that your intention is to beat yourself constantly—that you're in battle against yourself. This sort of cannibalistic self-competition...this is largely why people Britney out.

LK: I'm so glad Britney is finally a verb.

LG: And you can make it a gerund: "I was trying to avoid Britneying out." I think I'm really fortunate that this happened to me when I was in my late 30s, not my early 20s. And it happened on my fourth book, not my first. And it happened after I had already gone through a depression, a divorce, years of therapy, a lot of self-reckoning, a spiritual journey. I was in the lucky situation of knowing who I was. And, more important, who I wasn't.

LK: Meaning what?

LG: Meaning I'm not what's being said about me, either in the highest praise or the highest criticism. I know I'm not a self-indulgent idiot; I also know I'm not the second coming of Deepak Chopra. If I had believed either of those, or both, as some people do when they get famous, that's when the mental illness arrives.

LK: Do you sense with this book that people are expecting Son of Eat, Pray, Love?

LG: People want three things simultaneously from your next endeavor: They love what you did, so they want more of that. But they also want it to be totally different, because you have to show that you're reinventing yourself, à la Madonna. And they want it to be better. The same, different, and better. So, no pressure there. Done and done.

I remember being in English class in college and we were discussing To Kill a Mockingbird. And this pimply-faced 19-year-old boy next to me goes, "Harper Lee—one-hit wonder." [Laughs] And I was like, there's something wrong with that. This isn't a pop song; if you have written the definitive 20th-century tome on racism, compassion, and forgiveness, you can take a pass for the rest of your life, if you want to just garden after that. You know, it's crazy. It's just so nuts.

LK: Before this version of Committed, you had completed a 500-page manuscript that you ultimately trashed. What was wrong with it?

LG: When I went back and looked at the first chapter, I could see so clearly, even sentence by sentence, where it was my authentic, current voice, interspersed with attempts to delight and entertain millions of readers whose names I don't know, by throwing in stuff that I thought they might like. Strained attempts at humor. Strained attempts at goofiness that wasn't really going on during the year I was writing about. It wasn't a goofy year. It was a pretty serious year, you know? It just didn't sound right; it just didn't feel right. So I took some time off, and found that my mind kept going back to the marriage book, just thinking, "I do want to tell this story. I just have to give myself permission to hope that my readers will grow up with me."

LK: While the book is fundamentally about marriage, you are also quite frank about not wanting children, which had been a big problem in your first marriage. How did you reach that decision?

LG: Where other women hear that tick, tick, tick and they're like, Must have baby, for me, it was like, tick, tick, tick, boom. [Laughs] It was a biological clock, but it was attached to a bunch of C-4 explosives. I've often thought that if I had been married to somebody who wanted to be a mom, I could have done it. I used to say, "Man, I think I'd be a really good dad. I'll be a great provider. I'm funny; I'll go on trips with them—I'll do all sorts of stuff." But the momming? I'm not made for that. I have a really good mom; I know what she put into it. I didn't think I had the support to both have that and continue on this path that was really important to me. I wasn't married to a man who wanted to stay home and raise kids. So.

LK: You tell a story in the book that is pivotal for you, about your grandmother. She was born with a cleft palate and thought to be unmarriageable, so she got an education and took care of herself, one day rewarding herself with a $20 fur-trimmed, wine-colored coat, which she adored. Eventually she does marry. And when she gives birth to her first daughter, she cuts up the coat to make something for the child.

LG: That's the story of motherhood, in a large way. You take the thing that is most precious to you, and you cut it up and give it to somebody else who you love more than you love the thing. And we tend to idealize that, and I'm not sure we should. Because the sacrifice that it symbolizes is also huge. Her marriage and her seven children, in a life of constant struggle and deprivation—it was heavy. And that beautiful mind, that beautiful intellect, that exquisite sense of curiosity and exploration, was gone. I went to Africa when I was 19, and when I came back, I was showing her pictures. And I remember her stopping me and just—she had to collect herself. And she said, "I cannot believe that a granddaughter of mine has been to Africa. I just can't imagine how you got there." I think that her story is so central to my story. To be able to choose the shape of your own life—you sort of must do that, as an act of honor to those who couldn't. There were times, especially when I was traveling for Eat, Pray, Love, when, I swear to God, I would feel this weight of my female ancestors, all those Swedish farmwives from beyond the grave who were like, "Go! Go to Naples! Eat more pizza! Go to India, ride an elephant! Do it! Swim in the Indian Ocean. Read those books. Learn a language. Do it!" I could just feel them. They were just like, "Go beat the drum."

LK: There is a great part in the book when you describe how you knew your feelings for Felipe weren't just infatuation: "I did not demand that he become my Great Emancipator or my Source of All Life, nor did I immediately vanish into that man's chest cavity like a twisted, unrecognizable, parasitical homunculus."

LG: Like that little creature in Alien. [Laughs] Yeah. I'm very grateful not to be in that.

LK: But judging from your relationship with David in Eat, Pray, Love, you know what that feels like.

LG: Oh, yeah. I know exactly what that feels like. Talk about solving all your problems real fast: This person is the purpose of my life, and we have cycled through thousands of lifetimes to get to each other in order to complete this puzzle, across oceans of time...it's a Céline Dion song. But it's also a really aggressive thing to do to somebody—to impale yourself on them. And no wonder it often ends with one or the other person starting to feel suffocated and devoured. It's an assault, you know? How dare you not be what I—without very much of your help—decided you are! What an affront to me!

LK: You also talk in the book about loving Felipe so much that you want to protect him—even from you. So you proceed to come clean with him about all your flaws.

LG: It was like a preconsent form. A full-disclosure kind of thing. What I was so interested in doing in this whole story of our marriage was making sure that we were living in as much of a delusion-free zone as possible, having cultivated and spread delusion for so much of my romantic life, because it was so much more exciting and glamorous and thrilling than the truth. Certainly part of seduction is a masquerade, you know? One of the rules is that you don't show yourself. And I just didn't want that to be what was going on when we were preparing for this really big step. It's like, buyer beware. I'm 40; he's 57. We've been on the market a long time. And you should know: Okay, a little termite damage here. It's a pretty good house, but when it rains, it does flood the basement sometimes.

LK: I got a little anxious in the book when you say you're very disciplined about money and Felipe isn't, given that, during that moment in your relationship, you had yet to reap a huge windfall from the paperback of Eat, Pray, Love....

LG: Yeah, it's okay. It's okay. The good thing is, he's not a spendthrift. He's just somebody who has no respect for money. But I knew that we could handle it together. I'd had a lot of financial problems in my first marriage as well. But it was different, you know? I knew that Felipe and I could work it out.

LK: There is also the nervous-making part where you buy Felipe a pair of shoes, and new dishes, because you didn't like the ones he had.

LG: It's an irresistible urge for me. I don't know how not to do it: I have decided to renovate you. Slap a little paint on here, and do this. Fortunately, I don't think it's too extreme in our case. It goes along with the mend-and-tend urge that a lot of us have. So while I do those things, I also know that I come home every night and he's cooking me dinner, you know? I haven't been grocery shopping in probably six months. We're a good pair in that way, because I love to eat, and he loves to cook. We've been together five and a half years now, and I have never had that man put a plate of food in front of me where I didn't feel like I was in holy rapture. Because I never, ever, ever saw, in my entire life, a man bring a plate of food to a woman. Because it wasn't his job.

Taking that piece of it out, and also taking out the piece that he has to be the breadwinner, and that he wants to build a life here that's not as ambitious, and he's happy to scale that down a bit, then it's okay for me to buy him a pair of shoes.

LK: So your ex-husband, Michael Cooper, has his own memoir coming out next fall. Excited for the book party?

LG: We'll see if the invite comes. Honestly, it hasn't really affected me much. I really think that if anything, it's probably a healthy outlet for whatever complicated sorts of feelings he must be having about me right now. And I can't really blame him. Everybody has the right to tell their story. I obviously have exercised that right not once but twice. My sense is that he will tell a very different story from mine. But that's why we're not married anymore. A lot of what marriage is is the ability to agree on a central narrative, you know? And the shockingest thing about the divorce was, even after six months of therapy, it was like, "We do not agree on a single thing about what's going on here. We, the undersigned, can't even agree on where to sign on this page, so a judge is going to have to tell us." That's called irreconcilable differences. It's the reason people get divorced.

I really don't have a lot of hostility toward him. He's remarried, he's got kids, he's moved on with his life. I'm glad he's happy. I just—I don't want to live with him, you know?

LK: Now that you've been hit with this tsunami of cash, is there any threat that it might insulate you from the kind of rugged, spontaneous travel that made you famous?

LG: I've actually never traveled less than since I got hit with a tsunami of cash. When I was in Mexico when I was 20, I remember meeting this American couple who were in their 60s, and they said, "Oh, it's so great that you're traveling now, before you have kids, because you won't be able to then." I know this is a thing that people do; they go traveling for a year, and then they hitch their leash to the wall and put their face in their feed bag and that's the end of it. And I thought, "But I might want to keep doing this," you know? But it's been really interesting for me to see that everything I'm curious about right now is here.

LK: Eat, Pray, Love is being made into a movie starring Julia Roberts and Javier Bardem as you and Felipe. How surreal is that?

LG: It is exactly surreal. But there's an energy to Eat, Pray, Love that is so incomprehensible to me. Its expansiveness, and its reach—I sort of look at the book like, "You want to be a movie? Go be a movie. I didn't know you wanted to be all this other stuff, too." It's so much bigger than me, and I'm very happy to let it be that. "Go get translated into every language. Have at it!"

LK: And now, with Committed—having spent several years analyzing the institution of marriage, are you feeling hopeful about the institution?

LG: I think when I went into it, I saw it in a very narrow light: I saw it as oppressive and outdated. And stupid and useless. And possibly very, very destructive. And I came away thinking it's complex and long-lived. It must be here for a purpose, because it keeps being here. It's always evolving.

LK: Sometimes I feel like marriage is nothing more than a goofy social construct.

LG: We're goofy social humans. What other kind of construct could it be?

Keep Reading: What Elizabeth Gilbert knows for sure

Please note: This is general information and is not intended to be legal advice. You should consult with your own financial advisor before making any major financial decisions, including investments or changes to your portfolio, and a qualified legal professional before executing any legal documents or taking any legal action. Harpo Productions, Inc., OWN: Oprah Winfrey Network, Discovery Communications LLC and their affiliated companies and entities are not responsible for any losses, damages or claims that may result from your financial or legal decisions.